Coalmining in Wales has been represented in engravings, drawings, and paintings ever since it emerged as a cottage industry in the early 13th century. From the second half of the 19th century until its demise in the 1980s, what grew into a large and complex means of production became a significant genre in Welsh landscape art. However, little attention has been paid to the equally impressive and distinctive acoustic character of the industry. Until the development in the mid-1920s of electrical audio equipment able to record a reasonably broad range of frequencies in the sound spectrum, it was impossible to capture the collieries’ sonorities.

The innovation enabled the British Movietone newsreel company to make South Wales Colliers Go Down the Mine, which was released in 1930. Its subject is Penallta Colliery, which was situated near Hengoed in the Rhymney Valley. The movie represented the ‘first sound pictures of a British coalmine’. (‘Sound pictures’ referred to a cine film with sound effects and dialogue recorded on it.)

The first commercial sound movie, The Jazz Singer, had been released only three years earlier. British Movietone News’ ‘sound pictures’ were, therefore, not only still a novelty as far as the audience was concerned but also at the cutting-edge of new audiovisual technology.

The black and white cinematography of South Wales Colliers Go Down the Mine dignifies the colliers’ labour and dramatizes the pit’s machinery. The hewers and sifters look like animated versions of workers painted on an ancient Egyptian tomb. Pistons, cranks, shafts, and flywheels are made to appear immensely powerful, efficient, dangerous, and exquisitely beautiful — as indeed they were. Disciplined direction, astute editing, and an intelligently considered narrative conception enabled the movie to show and tell a story about ‘a shift in the life of’ the colliery, as well as explain the stages of coal production in some detail, in just over eleven minutes.

Unlike Pathé News (which began making documentaries and newsreels in 1910), British Movietone’s releases didn’t feature a disembodied and pervasive voice-over describing events on screen. Instead, the Penallta Colliery movie incorporates a series of explanations about how coal is extracted and processed, narrated by the pit’s Overman. In other words, someone who was in the scene and in-the-know. Apart from his interventions, the story is ‘spoken’ by the moving pictures alone.

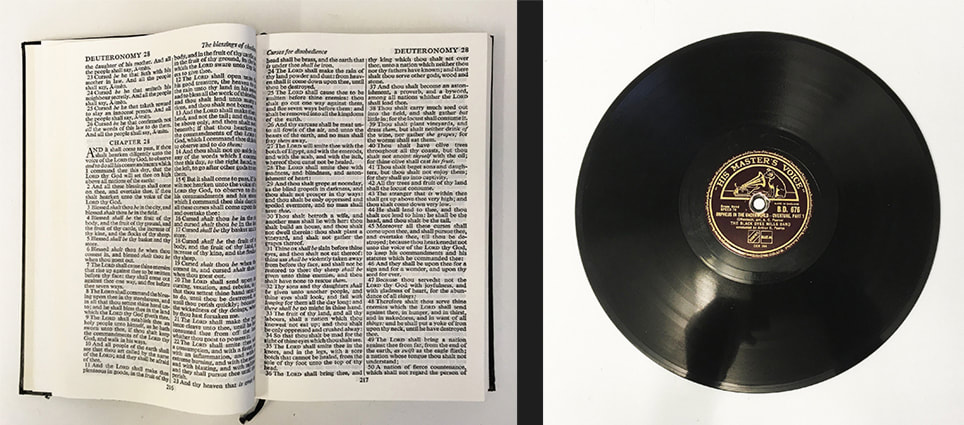

The movie also includes a variety of sounds associated with the working environment, including the noises of screen meshes, hydraulics, pneumatics, pit-wheels, drams, and cages in operation; the voices of colliers; as well as musical interludes that partition the movie’s chapters. These provided the raw materials for my suite of compositions. Several additional sources contributed to the works. For example, one track includes the aggregate superimposition of the sound of pages from the King James Version of the Bible being read, while some others incorporate small samples of sound content taken from a 78-rpm recording made by the Black Dyke Mills Band of Jacques Offenback’s Orpheus in the Underworld: Overture (1858), released in 1936.

I grew up in a coalmining community. My maternal grandfather was the Overman at Beynon’s Colliery, Blaina, Monmouthshire, and a chapel deacon. My paternal grandfather was a Winder at the Cwmtillery Colliery, Abertillery, and had been a Communist. As grandson of the ‘head honcho’ at Beynon’s Colliery, I was given the freedom of the pit. I drank tea in the colliers’ canteen, counted the canaries, and fed sugar cubes to the pit ponies. The heady blend of sweat, flux, oil, grease, and coaldust filled my nostrils. I could taste it in my mouth. Intoxicating. The sounds of the cage and its cargo of miners ascending and descending the pit shaft, the winding wheels in motion, the hooter that announced the beginning and end of shifts, the electricity generators’ terrifying 50Hz hum, the crack and spark of switches being turned on and off, and the clank of iron-on-iron as the coal trucks were shunted, made an enduring impression on my acoustic memory. The recollection of these sonorities contributed significantly to realizing the compositions’ emotional resonances.

The compositions’ themes neither follow the narrative development nor are restricted to the subject matter of the movie. The source had to be overcome for it to become something else. Rather, my aim was to create pictures evoked by sound and pictures made of sound. The tracks are based upon the movie’s soundtrack, principally. The album doesn’t engage with the cinematic dimension of the movie. However, its imagery strongly informed my approach to the interpretation and transformation of the sounds.

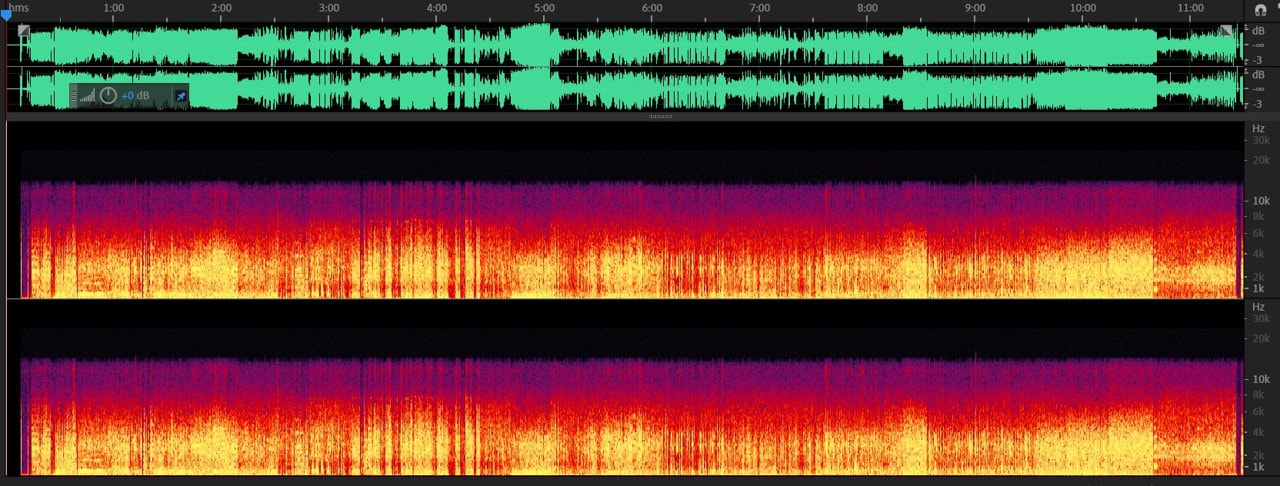

The movie’s sound quality also needed to be overcome. Movietone’s optical-sound film track had a sound frequency range of 8,500Hz. The high-definition digitized version of the original – which I worked with on this album -- has a somewhat broader range from 800Hz to 10kHz, occupying the high-mid to high frequency range. Sounds within the 31-700Hz range, which represents low-mid to low frequency range, are entirely absent. Many of the noises produced by colliery machinery occupy this part of the audio spectrum. Therefore, the film’s soundtrack could not do justice to the sonic reality of its subject. The soundtrack also has little dynamic range overall. Consequently, loud and complex sounds are rendered indistinctly. Often, it’s difficult to discern what is taking place in a scene without reference to the pictures.

Thus, even before working with the soundtrack, a restorative and interpretive approach to the sound -- tutored by the image -- was required. In order to extend the audio spectrum, I fabricated ‘false’ lower frequencies by dropping the original sound profile by up to two octaves, and re-recording samples acoustically through monitor speakers and a subwoofer. The enhanced sound profile was, afterwards, integrated with the original source.

The sounds were modified and rearranged by applying various digital methods and techniques, such as collaging, superimposition, inversion, stretching, and synthesis. Composition took place on computer software aided by equipment used by DJs. In these ways, the hardware of historical coalmining and contemporary music making coalesced.

The movie’s sounds were manipulated and arranged in such a way as to evoke imagery, structures, ideas, moods, contexts, and backgrounds suggested by the movie’s content. For example: the activities, people, processes, mechanisms, and places portrayed; the histories of the Penallta Colliery and South Wales coalfield; and aspects of the biblical and religious cultures that were inextricably bound up with colliery work and life during the 19th and early-20th centuries.

Having returned to research on coalmining after over two decades absence, I realized that my approach to this CD project, and the history of fossil-fuel extraction in general, had to acknowledge the current context of climate change. Since COP26, especially, the coal industry has become public enemy number one. Therefore, whatever romantic attachment we may still have to Welsh collieries, needs to be tempered by the realization that they contributed to the current environmental crisis. In this sense, Penallta Colliery: Sound Pictures is as much about our present and future as it is about the pit’s past.

John Harvey

June 2022

June 2022

Throughout the site, text in green indicates a hyperlink.